After a brief spell at the Christiania squat in Copenhagen, I went to stay with some old contacts in London, managing to pick up some part-time work before then moving to Cheltenham and from there to the south coast. I was drinking a lot, but I had started drawing again, gradually moving onto colour work with designs for glass panels. It was a straightforward extension of the sketches I’d done before, but rather than throw them away I had a sense that the work I was doing had value and was therefore worth keeping.

My mother’s relationship with my cousin was now over and she had moved house so I stayed there briefly while looking for a room to rent. It was the first time I had spent a substantial amount of time with her in nearly fifteen years.

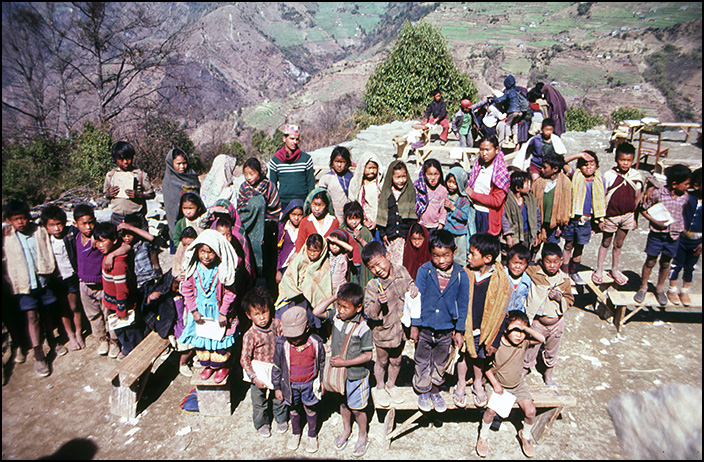

She had been taking adventure holidays in Nepal and wanted to go again but with a large group. I saw this as an interesting photo opportunity so we planned a trip for the early spring of 1983. Sixteen people, most of them pensioners, signed up to come along, and on the basis of the bulk flight and trek bookings I was given a free ticket.

At that time, I was working in a hotel bar and my mother had to give me the money to buy a camera. She fretted over the expense of me buying a single lens reflex, but I knew I could borrow some extra lenses to use with it which would increase its range. I kept the Pentax MV for nearly ten years and it served well.

Penny for the Guy

The trip was planned for February and March so I had plenty of time to practise on friends or just in the street. I hadn’t studied photography in a formal way but I wanted to record what I saw and create pictures that could stand as independent compositions. News photography and fine art informed my perspective. In Nepal I shot mostly colour slide film though the shots have not survived the intervening years very well. Apart from the Kodachrome most colour dyes could not stand up to frequent changes of temperature and humidity.

Shikha School, Nepal

It was the first time I had travelled on a holiday, rather than just following after a job somewhere. We walked from Pokhara to Muktinath, a small village at 10,000 ft and some 30 miles from the border with Tibet. We ate tsampa, barley porridge, and a lot of fried eggs and rice which kept me happy.

Back in the day, Nepalese cannabis resin had been the connoisseur’s choice. I had completely lost any interest as not only did smoking it increase the severity of the headaches, I also found it harmed my creative decision making when sketching or taking photographs. Nonetheless, when walking through one mountain village a young guy stopped me and showed me a lump of hashish he wanted to sell. It was about the width of my thumbnail, maybe 10 or 15 grams. It was black, soft and waxy, with a distinctive scent that had always reminded me of Marmite. I paid him a few rupees for it and put it in my pocket, for old time’s sake as it were. It was only when we took the return flight from Pokhara to Kathmandu that I remembered I had it with me – I surreptitiously dropped it into a waste bin just before boarding.

I wrote an article about the trip. Although it wasn’t published, I did succeed in getting one photo into a magazine. With that first publication under my belt I looked around for a photography course. I found the contact details for one in a nearby city but it turned out to be a dead lead and I wasn’t able to get hold of anybody to talk to.

I also started writing up the history of my earlier travels through Spain and France. While I was doing this I came across an advertisement looking for people who had worked abroad. I sent the publisher some of my writings and they showed an interest. In the end, Vacation Work only used a few quotations, but it was a positive outcome.

In the summer of 1983 I was given some hours working in a café through a friend which led to working for a vegetarian restaurant as a cook. I was living alone in a dilapidated caravan and had a three-wheeler Reliant Robin to get around in. Someone I’d met in Pune came over to stay and although she was a complicated and conflicted person we decided that we could help each other out. We moved to Paignton, then Hastings and then Cambridge where I stayed for five years.

I was thirty-one when I did a short training course to teach English as a foreign language. It made sense to me, as the years spent on the road in Europe had developed my ear for picking up language fragments from all points between Spain and Norway, and I had gained some understanding of the problems faced by the typical adult learner. Doing the course was like a holiday to me. It was a huge stimulus and as it happens, teaching turned out to be a lot easier than digging ditches or plucking farm-fresh quail. I determined to stick with it.

At the end of the summer, and after working at three different private language schools, I was advised that there was very little chance of getting a permanent job without a degree. This gave me a new goal. I had the three ‘O’ levels that I’d barely scraped through at school and the new teaching certificate, but if I was going to spend time and energy studying for say, an ‘A’ level, then it had to be a subject that I was enthusiastic about – but it was difficult to choose between this new language thing and the visual arts that I’d already invested time in.

I started going to regular life drawing classes, thinking that this was probably the best way of building up a portfolio to show people. Casual work came in the form of restaurant table waiting, kitchen work and house cleaning, which was hardly a great way to enjoy Cambridge at its best but it got us through to the next year.

One day in the late spring I wandered into the local college to see what courses might be available for someone aged thirty-two. I had a brief chat with an assistant on the desk and was given an appointment to go back and meet one of the tutors. I was given some reading and writing tasks and told to complete them before coming in for a formal interview. It appeared that the best option at Cambridge College of Arts and Technology was to aim for a BA Honours degree in Humanities and Social Studies.

I was interviewed for both the Art Study and English Literature courses which were offered together. It seemed remarkable to me that my portfolio, carefully built up over the previous year, was acceptable, as were my written essays. Even though I could not respond to any of the questions on 17th century Italian Renaissance paintings that I was asked at the interview, I was able to talk at some length about the sculptures of Henry Moore and Elizabeth Frink I had seen. I was offered a place, starting that October.

I was gobsmacked – I was effectively taking a sabbatical from real life in taking on a three year course on a full grant. In reality I still needed to work during the vacations, but that wasn’t likely to be a problem. The first year was demanding though not too difficult; one simply had to work out what standard of work was expected. There were a few other mature students on the courses but the majority were ten or so years younger than I was.

I was still living with my girlfriend when I started at the college but the cracks in our relationship were very evident. She was manic and a binge drinker, and the arguments between us were quite brutal at times. I was ready to move out at any minute but I patiently waited for her to pass her driving test on the fourth attempt, and waited yet further until one final tantrum forced me to look for other accommodation. I was lucky in finding a good room in a house quite close to the college. I stayed there for three years.

I spent hours at a time in the library. It was refreshing to discover the real pleasure of discussing ideas again, and having the time and materials to work on sculpture. The college supported this as a chosen specialisation, and Douglas Jeal, a sculpture tutor who had previously worked for Sir Anthony Caro, was consistently helpful.

Visiting the Contemporary British Medals exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge in 1986, curated by Mark Jones of the British Art Medal Society, was an eye opener and my immediate response was to try this out for myself. A medal is a small two-sided piece of relief sculpture which allows for a broad range of approaches, and since the majority are circular it reflected the small castings and glass designs I had done years earlier.

A well-designed medal could parallel a sonnet or a concerto in miniature. I found it intriguing because it combined purely visual and graphic qualities with the tactile depth of sculpture, yet it could also engage a poetic sense through the use of text. It was sufficiently complex in the making processes to be a challenge of both craft and artistry.

Commemorative Medal for the Victims of Apartheid

The third medal I made, Commemorative Medal for the Victims of Apartheid, was for the RSA Design Bursary Competition in 1986. The money I received as first prize was enough to fund a study tour of northern Italy the following summer.

I had not been to Italy before, and since it was to be a study tour I had a good reason to try learning a little of the language beforehand. I flew to Genoa and made my way across to Verona, Padua and Venice, visiting exhibitions, museums and churches – above all, churches, as I had been fascinated by medieval relief sculpture, in particular the bronze church doors. I went down through Bologna and Florence and from there to Rome. Only once, just outside Verona, did I have to use some of my road skills and sleep in a barn.

I met up with some of my summer school pals in Florence and Rome and visited an established medallic sculptor, Bino Bini, along the way. The four days I spent in Rome gave me ample time to study the reliefs of Giacomo Manzù, someone that David Baxter, my art history tutor in college, had recommended I look out for. I absorbed Manzù as deeply as I could, along with the works of Donatello and the Pisano family that I had found along the route.

I was still using news photographs as a source of inspiration, but now I added a flavour of the Romanesque and Gothic I’d seen in Italy. Coupled with a concern about ecology, I drew, painted and sculpted animal forms, orang-utans, and birds, as well as the occasional portrait head. At the same time I was listening to the Andy Kershaw radio programme and discovering new musicians from all over Africa. It was inspiring.

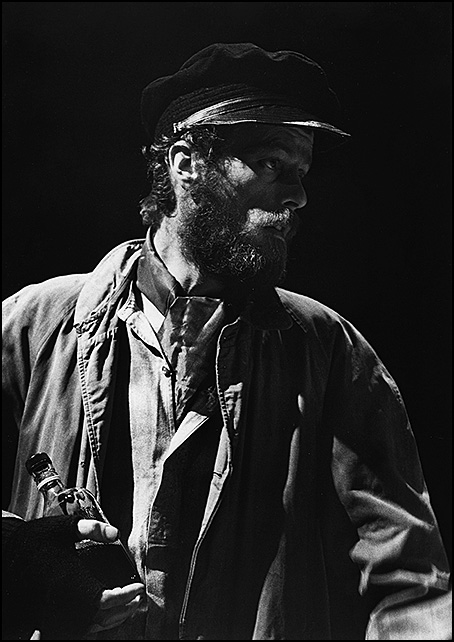

While at college I took on some stage acting at the Mumford Theatre. For the second play, Edward Bond’s The Sea, a guy called Bruce Herrod handled the stills photography. Jillie, the stage manager, introduced me to him and while talking with him about photography I mentioned that I had been trekking in Nepal three years earlier. Bruce was intensely interested and spent several days looking through my slide collection. He was already familiar with photography in extreme conditions having been an expedition member of several geophysical surveys in Antarctica but he told me he was hoping to get to the Himalayas quite soon.

Bruce shot the dress rehearsal and there was one photo in particular he was proud of, printing a couple of large versions. I was also very pleased with it as it captured an insightful view in the best character role I’d had, that of Mr Evens. Stage lighting can be difficult to work with, but it can also create strong contrasts, serving to isolate the essential details. This was cinematic photography in the tradition of Hitchcock or Orson Wells.

Mr Evens

Sometimes the topic of why a photograph might be important comes up, or indeed, why any photograph matters. The response will always be partly subjective, in that a photograph may be significant to one person or to one culture, and not to others. But Bruce took a self-portrait that would be important to everyone who knew him. Were it not for the Web I might never have discovered this, but he later made several trips to Nepal and eventually joined a group that took him to Everest. His last shot may have been his finest portrait as it shows the beaming smile of achievement as he rested for a moment among the flags on the summit of Everest. Thirty minutes later he was dead, probably from missing his footing as he descended. His camera was retrieved the following year.

Bruce

The academic work was satisfying and for my dissertation I wrote a piece on the role of relief art in the Modernist age. The basic premise was that most of the better known painters and sculptors in the Western world had used the relief format at some point. However, even though it was often experimental and sometimes might inform their later work in painting or in sculpture their work in relief tended to be ignored by most critics. I wanted to discover why it was under-rated.

I spent as much time as possible making new things. Although many pieces of work ended up in the waste bin en route to the landfill I photographed everything. I could experiment with different methods for mould making and casting, though I also learned how easily the waste pipe of the sink could become blocked with wet clay. I cycled everywhere, and ate ratatouille, cold out of the tin.

Completing the degree brought a sense of relief and I received a ‘first’ for my sculpture exhibition. The work had been stimulating but I had been living in Cambridge for five years and it now felt limiting. I didn’t make it to the graduation ceremony as I had a cold and was too sick to go anywhere that day, but I got one note in the mail from a relative, scribbled in pencil on a torn-off scrap of paper, congratulating me on passing.

I looked at the options open to me. I had no wish to do a post-graduate teaching certificate as I could not bear the thought of working in a school, so I applied for a couple of Master’s courses for sculpture. In 1988 there weren’t many to choose from. Douglas wanted me to apply to the Royal College of Art in London, and though we visited the studios I resented the idea of them charging a fee just for an application to be considered. I didn’t get any offers. Instead, I took a job with International House to teach English through the summer.

I hadn’t gotten anywhere with anyone over the last two years at college and the way I was looking at women probably meant I didn’t need a T-shirt saying, “I AM AVAILABLE”. It was perhaps inevitable that it would be one of my language students who would catch my eye, and for once the feeling was mutual and reciprocated.

Holiday romances are problematic as after a few short weeks she flew home, some 2000 kilometres away. But our interest was strong enough to keep it going, with visits in both directions over the following year. I took a full time job teaching at a language school in Cambridge and started making plans for a move to Italy.

Mr Evens and Bruce, Copyright ©1986 and ©1996, the Estate of Bruce Herrod.

| Early Days | Late Teens | Bilbao to Copenhagen | London to Cambridge |

| Bologna to Swansea | Salalah to Singapore | Wales | Untitled, Unfinished |