Bologna was important to my development in a number of ways. Not only was my third ‘marriage’ more fulfilling, it also left deeper scars when it ended. This was the first time I had become a part of a family, but it also made me aware that compatibility in mental health was at least as important as shared interests with a partner.

I had been in Cambridge for five years and had done any number of jobs during that period; this time, and it was a first for me, I was to stay in one place for five years and stay with the same company.

I lived at three different addresses in Bologna. The first was a shared house but it wasn’t a legal sub-letting and the landlord, Carlo, was caught out by the council and had to ask me to leave. The second was a converted storeroom in the courtyard of a medieval townhouse. It was a small room with a small extension for the bathroom and kitchen. I could almost sit on the toilet while doing the laundry under the shower and flip an omelette on the stove, without moving an inch. For the final two years I had a bedsit with the shower in a separate area, perhaps 13 square meters in total, but with the mainline train tracks running behind the house. At least the address was good – via Donatello.

However, I also had to travel for the job as I was running the teacher-training programmes and starting up new courses in other cities. I had the opportunity to stay two months in Florence and Arezzo as well as several weeks in Sardinia. There were regular trips to Modena and Piacenza to work on courses and to Forlì and Udine to carry out inspections.

In 1990, quite a lot of the work was on a contract to teach the Italian Police. In the main they were keen but some of the older students who had never studied had great difficulty with the word order of English, particularly with questions. But they were motivated; at least, they were determined to learn the swear words. It’s usually good practice to combine elements that a student must learn with those features that they want to learn, so it seemed helpful to clarify the distinction between ‘fucking’ and ‘the fuck’. Conveniently, this tied in very well with their grammar practice of the present continuous and before long they stopped asking questions like, “What, you are looking at?” and “Where, you are going?” and came out with the correct forms as in:

“What the fuck are you doing?”

“Where are you fucking going?”

“Who the fuck are you fucking looking at?”

Teaching at the language centre included working with groups, individuals, and intensive immersion courses for students. Doing English for Special Purposes, for example, covered a wide range of topics as generally the student would be the expert in their field but need help with their expression. We could guide them on pronunciation and intonation, on using the telephone or giving presentations, and all the while the teachers themselves would be learning about heart disease, European tax law, food chemistry, advertising, 3D computer modelling, mechanical engineering, or any other specialist topic you care to name.

The immersion courses required two teachers for some classes, which had its own hazards. We generally stayed with the company handbooks but not all of them were written in a clear and unambiguous style. They were good, but you could sometimes find an excessive use of words like rod, shaft, slip, plunge, lubricate, glide, vibrate, and so on, all together in a single paragraph on engineering, such that it became a strain for the two teachers working together to silently split their sides without cracking their faces.

Although low paid, it was a fun environment to work in and getting to know teachers working in half a dozen different languages was interesting. We were a strong team.

It was in Bologna that I finally got a diagnosis for a problem which had been slowing down my activities for at least three months each and every year. ‘Cluster Headache’ is a misnomer, as an attack does not resemble any kind of headache that you would associate with say, a hangover or eyestrain, a migraine or a lack of sleep. Rather, a major nerve in the skull is squeezed by a pulsating blood vessel, and the nerve screams in response. The pain simply shuts you down until the blood vessel relaxes again. A string of doctors, neurologists, and alternative therapists had failed to identify the disorder, but my local medic in Bologna, Dr Bagnoli, correctly diagnosed the problem and prescribed a suitable medication. It was a turning point, for while the problem did not disappear and has remained ever since, at last it could be controlled.

I worked on my sculpture in my free time, buying art magazines, talking to galleries, and entering competitions. It wasn’t very satisfying, even winning competitions was frustrating as by and large they were small provincial affairs and didn’t lead anywhere. But I was able to do some interesting sculptural pieces including a complete chess set of bird figures and I had some items cast in bronze and silver. In the end, living through Italian meant that I was again expressing myself far less than I needed; my Italian was good, but not good enough.

When I was 42 I left Bologna. I had been accepted to do a one year MA in Sculpture Studies at Leeds University. Whether it was emotional instability or reverse culture shock I can’t say, but when I arrived in Leeds I realised that this was not the course I wanted to do. There had been another offer to do an MA in Design at Glasgow, and as a more practically oriented course I felt it might have served me better. But I was too late for that year.

I went up to Edinburgh for a conference of the British Art Medal Society as I’d been working on a commission that they had just published. This was a bronze medal of Asterix and Obelix from the Goscinny and Uderzo comic strips. Goscinny saw a copy and according to the publisher’s secretary, “il l’a trouvée très bien réalisée”. It felt great that it was being exhibited at The Scottish Gallery, but this was also the first time I had been able to meet up with other sculptors and medallists, historians, critics and medal collectors.

Asterix and Obelix

Getting them cast was problematic as I’d based my price quotation to the Society on a sample cast by a small foundry that did funereal bronzes for the cemeteries in Bologna. The quality of the bronze was excellent and the cost very reasonable. However, when the founder did fifteen copies for me he used a different moulding technique, stringing them together into a gate assembly rather than doing them one by one. The loss of detail due to surface shrinkage was appalling and I could only reject them and go elsewhere, to professional art foundries that charged a whole lot more. Thirty six copies were commissioned and I barely broke even.

It was at this point my mother decided to sell up and move into a retirement home and she divided up her assets between the children. It was a practical decision on her part and one which allowed me to start looking for a house to buy. I don’t begrudge her frequent house moves and doing what she thought best, but at the time of the sale her assets were worth only half what they would have been had she kept the big house near London.

I had no reason to stay in Leeds and started looking for ways to move further south in the UK; I eventually settled on South Wales. Britain was just coming out of a recession, property prices were depressed, and I picked up a small converted stable for very little money. It was August when I moved, which left plenty of time to strip out the dead plumbing and install new radiators before the winter. I put in new wiring and lights and a set of windows and got just enough done to make it habitable.

I didn’t get everything right. About a year after I’d fitted new joists and put down new flooring upstairs something made me look at the surface of the floor a little more closely. I was sitting on the bed staring at the stencilled black ink on the chipboard under my feet. Maybe at first I hadn’t realised that this was actually writing and not just a code number, but scrutinising the text more closely I could see that it said, “This Side Down”.

I was also taking the time to learn how to type. While my fingers and the palms of my hands were well trained in holding and using tools, my fingertips were less finely controlled. Following a book of exercises I worked up to twenty words a minute in just a month, which might seem quite a dull way to pass an hour but for the fact that I could now express myself with less effort. All of my first degree essays had been hand-written draft by draft, but word-processing allowed for edits on the fly which was liberating.

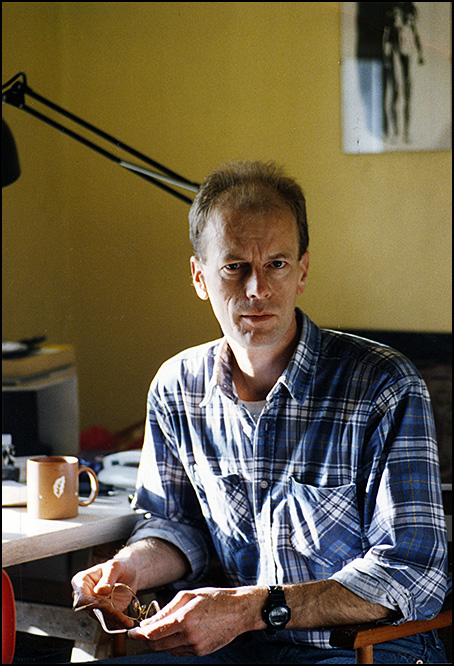

Self

It was a process of slow and methodical change as I immersed myself fully in restoring the house and searching out commissions for sculptural work. I worked on a couple of portrait medal commissions for Thomas Fattorini in Birmingham. This was satisfying and well-paid work, but there was really very little of it. However, it gave me the time to create a line of small outdoor sculptures that were reviewed in The Daily Telegraph Magazine and sold quite well. During 1996 I was able to exhibit my pieces at a number of venues across the UK, but it was always at a cost even when I sold work.

As the year wore on I started sculpting for a model-making company just outside of London. They were contracted to create figurines for Disney in Paris and were able to pass jobs on to me by post. Apart from the money I felt it would be useful practice to keep my skills up, though it did strike me as bizarre; I had studied Donatello, and Rodin, and Henry Moore, at length and in great depth but I was now making fridge magnets of Mickey and Mini Mouse.

In reality, I found making the figurines quite challenging as I was working to a very tight brief, and when it came to creating three Dalmatian puppies as merchandise for a new Disney film, we realised that it was time to part company.

I had to look for employment again as the overdraft was becoming unsustainable. Flipping through The Guardian I spotted an advert from a language school I had worked for in Cambridge. “Can you be in Oman in ten days?” was the extent of the interview. It didn’t take ten seconds to work out that I could. The job would quickly resolve the financial problems though again it would mean a change of direction.

| Early Days | Late Teens | Bilbao to Copenhagen | London to Cambridge |

| Bologna to Swansea | Salalah to Singapore | Wales | Untitled, Unfinished |